Women and Precarious Employment: A spatial analysis of economic insecurity in Cairo’s neighborhoods

Women face major disparities, compared with men, in the Egyptian labor market. In the Greater Cairo Region, jobs are less available for women and they tend to be of lower quality. These discrepancies are particularly apparent at the lowest administrative level, the neighborhood or shiyakha. While in some neighborhoods women have higher labor force participation rates than in others, across the board women work in temporary jobs at a higher rate than men. Temporary jobs–contracts that can be as short as one day according to the Egyptian labor code–offer little by the way of job security and employers are not obliged to provide any of the benefits or labor protections that ‘permanent’ workers enjoy. In this brief, we focus on temporary employment to dissect the gendered aspects of precarious employment in neighborhoods across the Greater Cairo Region. Precarious employment has little to do with the sector or type of job; rather, precarious workers are those who occupy a particularly vulnerable place within the economy. Rodgers and Rodgers define precarity as:

(1) the degree of certainty of continuing employment; (2) control over the labor process, which is linked to the presence or absence of trade unions and professional associations and relates to control over working conditions, wages, and the pace of work; (3) the degree of regulatory protection; and (4) income level (1989, p. 11).

Precarity is not new, yet the adoption of neoliberal policies has reorganized work across the globe, producing ever greater vulnerability in employment. Because the neoliberal ‘Washington Consensus’ stressed the shrinkage of the public sector in favor of privatization, it has had a disproportionately harmful effect on women’s employment worldwide. In the Egyptian context prior to neoliberal reforms, most employed women worked in the public sector. As the state shrunk, so did women’s employment opportunities and secure jobs. In the early 1980s, the “proportion of female new entrants finding employment in the government had been as high as 55 percent” (Assaad 2015, p. 3). For those with a secondary education or higher, the proportion was over 80%. By the early 2000s, however, only 20% of women entering the workforce found public sector employment. The mid 2000s saw a slight rebound up to 35% but women’s employment opportunities in the public sector have never completely recovered (Assaad 2015, p. 4). It is unlikely that public sector opportunities will return. Although privatization does not necessarily shut out opportunities for permanent jobs and decent work, the Egyptian labor law as it stands now provides employers with discretion to hire and fire at will and keeps many workers in a permanent state of instability.

In the case of Egypt, neoliberal reforms gradually removed the employment protections offered by public sector government work. Prior to and during the Nasser era, the government implemented policies which provided a degree of job security for workers, including a fixed minimum wage and sick leave, and equal working conditions in the private and public sectors. Although there was some negotiation between the government and organized labor, the only legal labor union is the Egyptian Trade Union Federation (ETUF). The board of the ETUF is appointed by the Egyptian government, all local unions must be affiliated with it, and many workers see it as simply an arm of the state which co-opted the struggle for labor rights. Private unions made an appearance before and during the Arab Spring of 2011—municipal tax collectors were the most successful at organizing and winning concessions, which is no surprise given that a tax collector strike puts greater and more direct pressure on the government than a strike by factory workers. Factory worker strikes were routinely repressed in the years leading up to the Arab Spring. However, private union organizing has disappeared in the years since, and the ETUF remains the only venue for labor negotiations. In spite of the fact that the ETUF does not provide a truly free space, workers did achieve a modicum of rights prior to neoliberal reforms, rights that they won in a long struggle spanning decades. Beginning with Sadat’s Open Door Policy, the state began to systematically disassemble these rights and workers steadily lost protections throughout the 1990s with the Economic Reform and Structural Adjustment program. Changes in labor laws in the early 2000s reneged on the previous, although imperfect, social contract of the Egyptian government with its people.

The main thrust of these policies was privatization, and their stated goal was to create a “flexible labor market” that would encourage economic growth. Governments slashed regulations put in place to protect workers and sold off government-owned businesses, privatizing both the economy and the social safety net. This ‘flexibility’ relieved the government of the responsibility to provide basic services and gave power to companies to fire employees at will and cut their benefits.

In 2003, the Egyptian government passed Law 12 of 2003 (Unified Labor Law) which introduced temporary contracts in an official capacity and many have argued that such contracts fall short of the ideal of decent work. The ILO defines decent work as employment that is “productive and delivers a fair income, security in the workplace and social protection for families, better prospects for personal development and social integration, freedom for people to express their concerns, organize and participate in the decisions that affect their lives and equality of opportunity and treatment for all women and men” (n.d.). Again, central to the issue is precarity and uncertainty in the labor market.

A temporary Egyptian worker at a recently privatized textile factory described his situation in this manner:

If I’m sick I don’t have health insurance to cover the expenses. With LE 350 [about US$19.50] a month how can I pay for healthcare? How can I live and pay for medicine? I’ve been working in the factory for two years. But, it’s a temporary solution, as soon as I find something better I’ll leave. Permanent workers have rights that we don’t, such as bonuses and incentives. I only have my [basic] salary to live on. But we do the same job. We produce as much. The new management created this unequal system (The Solidarity Center, 2010, p. 154).

This captures the reality of what workers are facing on the ground and women disproportionately face these sorts of conditions. Economic reform packages and development policies sell themselves as encouraging labor force participation for women, both as a means of growing the economy and for the purpose of ‘female empowerment.’ Yet there is nothing empowering about vulnerable employment.

In the first section of this brief, we discuss female labor force participation rates and unemployment in the Greater Cairo region, comparing these figures to global and regional figures. We then scale back down to the local level, comparing male and female unemployment rates across neighborhood boundaries in the GCR, which shows that opportunities to participate in the labor market vary from place to place, with women struggling the most to find employment. When we compare men and women working in temporary jobs, we see that when women do find a place in the labor market, they often find themselves in vulnerable employment at a much higher rate than men experience.

We then take a look at the neighborhoods where women work in temporary jobs at extremely high rates. The fact that neighborhoods vary dramatically in their labor force participation rates, unemployment rates and percentages of workers in temporary jobs tells us that geography plays a clear role in shaping the chances for obtaining decent work. Complete spatial equality in the labor market would mean that where a person lives would not determine job opportunities, and the security, compensation and benefits those jobs provide would not vary dramatically from place to place. Although we do not have enough information to provide a highly detailed picture of what the labor market in each neighborhood looks like, such as the types of industries or sectors that are concentrated there, we can use the relationship between labor force statistics, temporary contracts and the socioeconomic characteristics of neighborhoods to make inferences about the degree of precarity in the local labor market. We find that precarious employment is much more prevalent in some neighborhoods than others, and in some places, its effects are quite pernicious. Variation in precarious employment from neighborhood to neighborhood is evidence of spatial inequalities in the labor market, which we find are closely related to spatial inequalities in the distribution of wealth. Most importantly for our purposes in this brief, there is a highly gendered dimension to these spatial inequalities: comparing employment outcomes for men and women shows us that women find themselves in the most precarious positions in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods. In other words, the intersection between gender and geography breeds further inequalities, limiting chances for women’s economic mobility.

Our data is from the most recent available Egyptian census, conducted by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS) in 2006. We hope some of the conclusions may be updated as soon as the 2017 census data becomes publicly available. This additional data will allow an analysis of change over time, which will help us trace how increasing poverty rates and inflation have affected individual neighborhoods and employment opportunities for both men and women. Given that economic conditions have deteriorated since the 2006 census, it is likely that the spatial disparities we have found here have only widened.

Labor Force Participation & Unemployment for Men and Women: Global, Regional, and Neighborhood-Level Comparisons

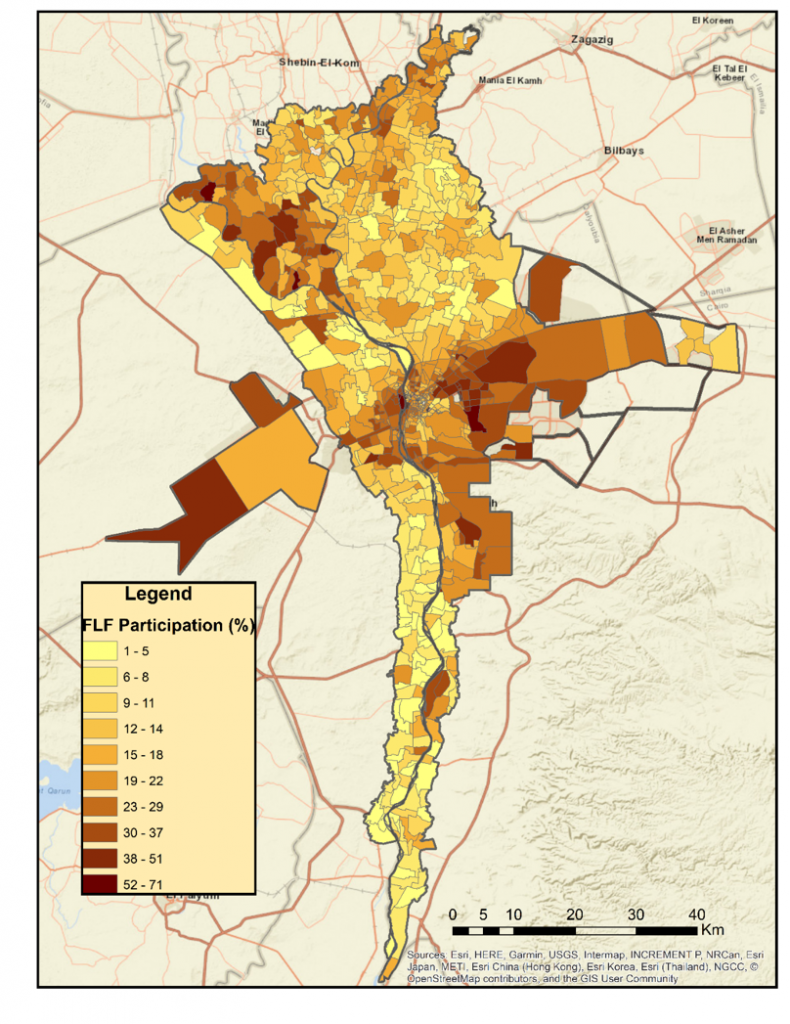

Women’s labor force participation varies from less than 2% to just over 70% from neighborhood to neighborhood within the Greater Cairo Region. From Map 1, we can see that at first glance, there appears to be an urban-rural divide, with the exception of the rural areas in the northwest. These neighborhoods are characterized by higher female participation in the labor force than the rural areas further east, and much higher than the rural areas in the south where female labor force participation is extremely low. The mean for all the neighborhoods is quite low, at approximately 17% female participation in the labor force. Overall, in 75% of the neighborhoods in Cairo, female participation in the labor force is below 22%.

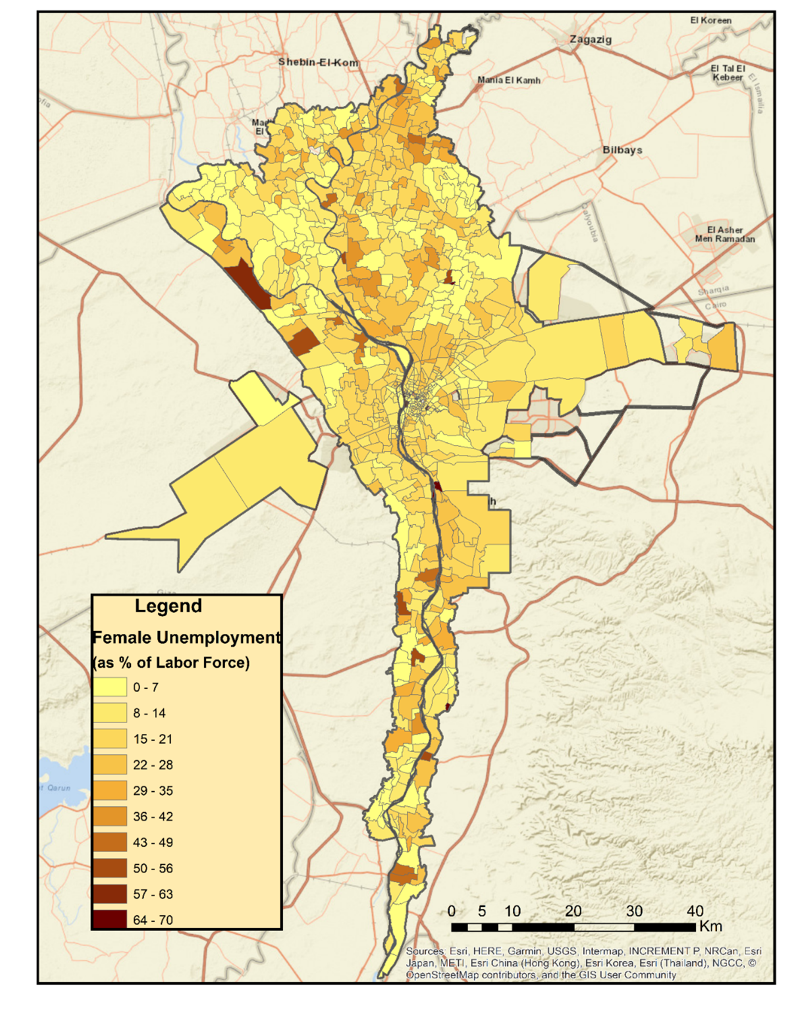

At the same time, the average unemployment rate for women is about 15%. Map 2 shows the unemployment rate for women as a percentage of the total (female) labor force. While there is some geographic variation, the majority of neighborhoods are close to the mean, but there are a few neighborhoods that have extremely high unemployment rates. The range of women’s labor force participation is similar to the range in women’s unemployment rates, but there is much more variation in the former than the latter. In some ways, this map masks the true level of inequality between places. At first glance, because so many neighborhoods fall between 0 and 20% (which is still a very large range when it comes to unemployment statistics) the map appears largely monochromatic. However, when we look at the scale and see that the darkest areas represent neighborhoods where unemployment rates are more than 50% and sometimes as high as 70%, we begin to get a sense of just how many barriers to the labor market there are in some places compared to others, obstacles that do not seem to exist to such a degree in the vast majority of neighborhoods. In fact, many of these neighborhoods with extremely high unemployment rates are adjacent to neighborhoods with the lowest levels of unemployment. So although there is less variation in unemployment than labor force participation, the extremely high rates of unemployment in particular neighborhoods point to real spatial inequalities between places, as certain neighborhoods have labor markets that are extremely inaccessible to women seeking jobs.

Importantly, the unemployment rate does not take into account people that are not actively looking for work or have dropped out of the workforce altogether (they are defined as inactive rather than unemployed). We do not have enough data to calculate the number of women in Cairo who do not participate in the labor force but are excluded from unemployment statistics because they are not currently seeking jobs. However, because women’s labor force participation rates are so low and unemployment is not astronomically high to “make up for” the discrepancy, we can conclude that a large percentage of women in the GCR are simply not part of the labor force. A recent study of youth labor force participation rates in Egypt, Jordan, Tunisia, Lebanon, and Palestine found that on average, 28% of women aged 15-29 are inactive non-students (Dimova, Elder, & Stephan, 2016, p. 23). In Egypt, 40% of women are inactive non-students, the highest percentage in the study. Unfortunately, this information is not disaggregated to the local level, so we cannot identify the spatial disparities of leaving the labor force. Since those that are inactive are not included in unemployment statistics, this obfuscates the full scope of the problem.

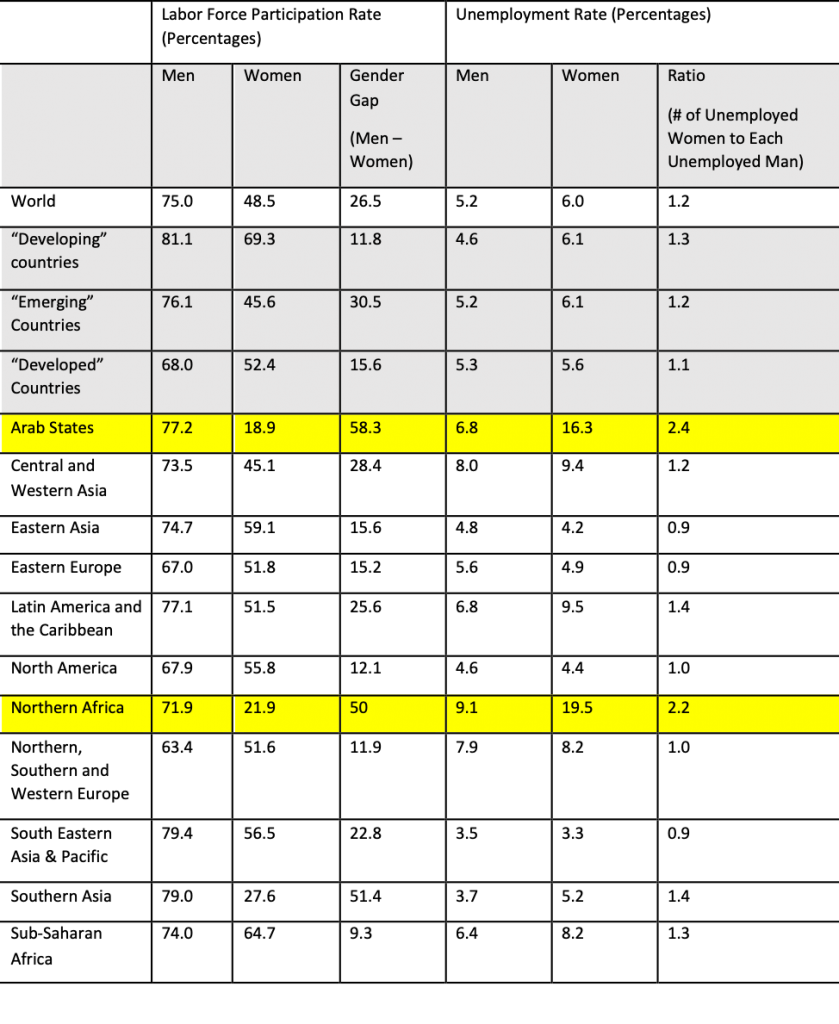

Still, the average rate of 15% female unemployment is troubling when we consider that the global average currently stands at 6%, a figure that has actually increased in recent years. The average neighborhood-level female labor force participation rate of just 17% in the GCR falls far below the global mean of 48.5%. Table 1 provides a cross-regional perspective on labor force participation rates and unemployment rates for men and women. Female labor participation is typically higher in lower income counties than anywhere else: while nearly 70% of women in the “developing” world participate in the labor force, only about half do in “developed” countries (ILO 2018). The reason for this has to do with economic necessity. In higher income countries, women have somewhat more agency to choose whether or not they will seek out employment. As a middle-income country, Egypt is typically classified as an “emerging” economy. In emerging economies, there is somewhat less of an economic necessity for women to participate in the labor force compared with low-income countries, but employment policies typically lack the protections for women (particularly surrounding pregnancy and maternity) that facilitate and incentivize women’s work in high income countries. As a result, the rates of female labor force participation are the lowest in middle-income countries. Even so, female labor force participation rates in Egypt—and specifically the Greater Cairo Region—are far lower than those of comparable economies. The average rate of female labor force participation in emerging economies is 45.6%, approximately 28 percentage points higher than the average female labor force participation rates in the Greater Cairo Region.

The situation in the Greater Cairo Region mirrors larger trends in MENA countries. We can see from the figures on Northern Africa and the Arab States that the region continues to lag behind the rest of the world. There are also much larger gender gaps between men and women than in any other region except for Southern Asia. The gender gap in labor force participation (the difference between the rates for men and women) is 50 percentage points in Northern Africa and nearly 60 percentage points in the Arab States. MENA countries also have the highest rates of unemployment for women globally: 19.5% in Northern Africa and 16.3% in the Arab States. The Middle East and North Africa is the only area of the world where there are more than two unemployed women for every unemployed man.

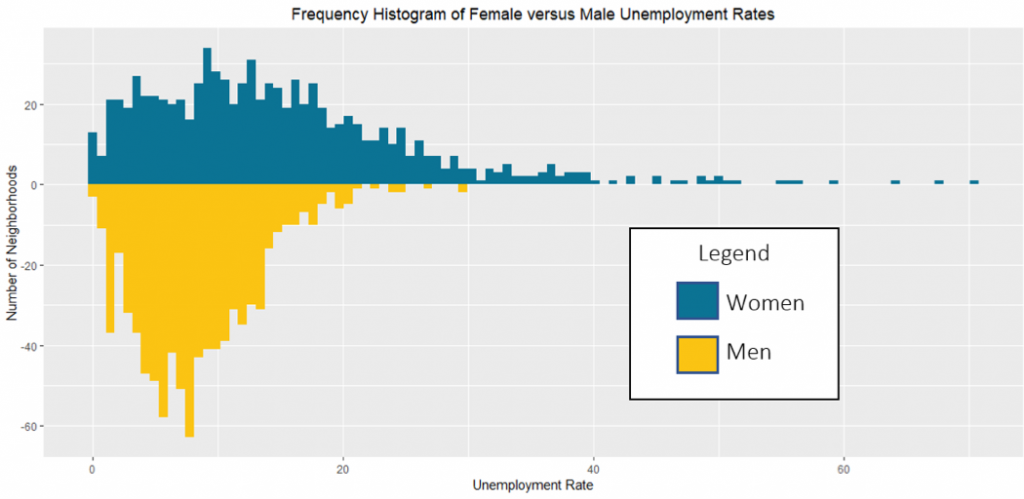

Scaling back down to the Greater Cairo Region, the rates of unemployment vary neighborhood-to-neighborhood for both men and women, which suggests that where one lives plays a role in determining employment outcomes. Figure 1 displays the distribution of unemployment rates, or the number of neighborhoods at each level of unemployment. While there is a stable and relatively low average of male unemployment at 8% in the GCR, unemployment rates are not only higher on average for women, but there is a wider range between neighborhoods. In three-quarters of the neighborhoods, the male unemployment rate stays below 11%. The highest unemployment rate of any neighborhood is about 30%; however, there are very few neighborhoods near this value. For women, the average unemployment rate is much higher at about 15%, and some neighborhoods are as high as 70%. These are the neighborhoods that stood out in Map 2, above. The wide range displays a shocking disparity in employment opportunities offered to women, and we can see that there are many, many neighborhoods where the unemployment rates are much higher for women than they are for men. Looking at the top half of Figure 1, the neighborhoods to the right of the 30% mark have unemployment rates for women that are higher than any neighborhood-level unemployment rate for men in the entire GCR. The increased difficulty women face in obtaining employment is likely related to the decline in public sector job availability, but may also be influenced by the types of industries that exist in the neighborhood and the barriers women face in certain employment sectors.Table 1: Global Comparison of labor Force Participation Rates and Unemployment Rates for Men and Women 2018. Source: ILO

Temporary Jobs

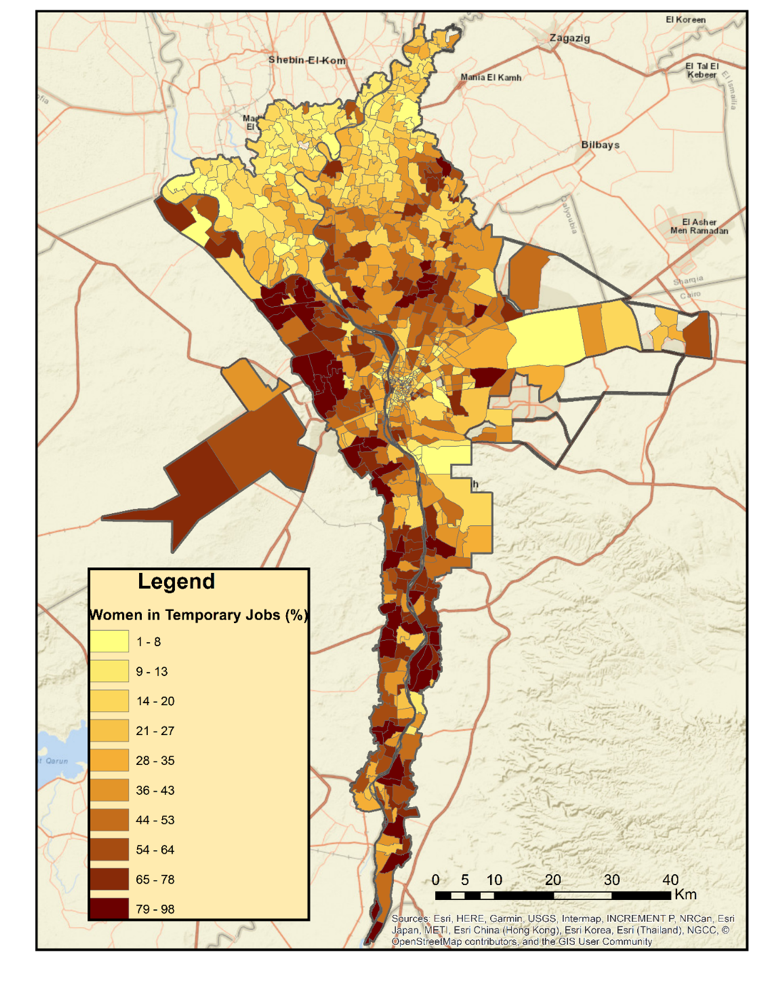

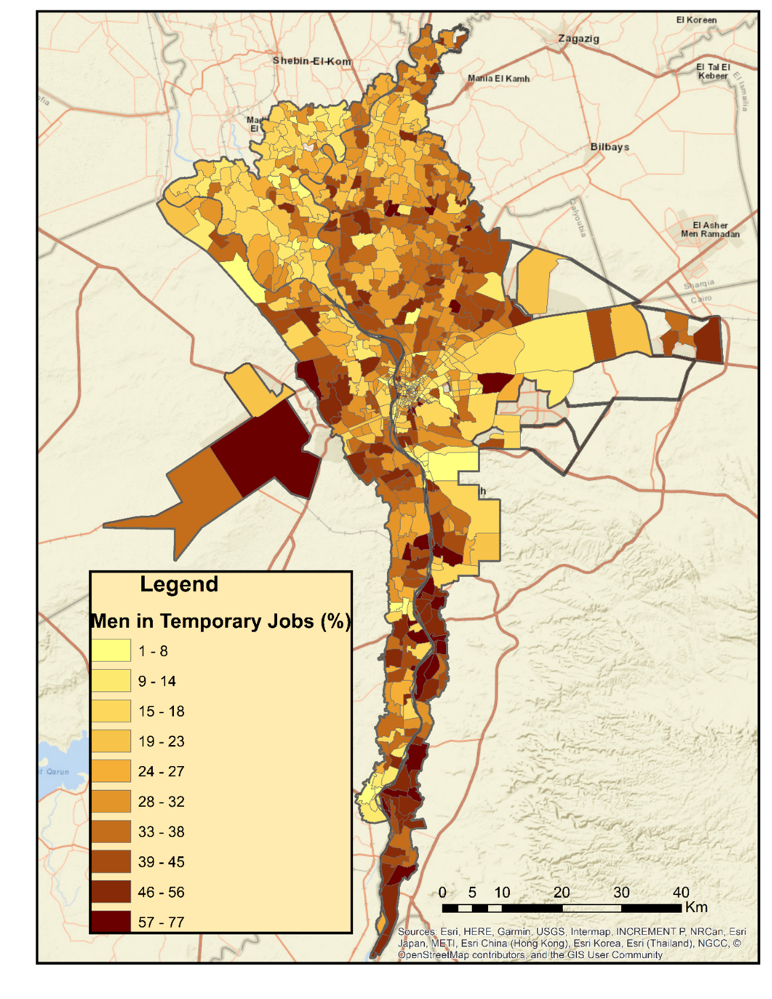

Even when men and women do find jobs, permanent jobs and decent work are hard to come by, as we can see from the high rates of temporary jobs throughout the GCR. Maps 3 and 4 show the percentages of women and men in temporary jobs respectively. These maps allow us to see that in neighborhoods where high percentages of women are working temporary jobs, men are doing so as well. This shows an overall spatial disparity in the labor market, where in some neighborhoods temporary jobs are largely the only opportunities available.

Although the largest concentration of temporary jobs (for both men and women) appears to be in the southern half of the GCR (Helwan), there is not a clear pattern here. There are neighborhoods with high rates of temporary employment in both urban and rural areas. It is only in the north-westernmost part of the GCR and the sparsely populated new cities in the east that we see large sections where rates of temporary employment are low, and this is true for both men and women. But even here we see variation, with some neighborhoods in these sections showing high rates of temporary employment, standing out against the yellow and light orange areas. Although it is difficult to discern an overall geographic pattern, what we can say based on the fact that there is a lot of variation between places is that there are spatial disparities at the neighborhood level. In some cases, neighborhoods which are adjacent to one another appear to have very different labor markets and employment outcomes.

While comparing the maps tells us temporary jobs are more common in some places than others, on the whole women work in temporary jobs at higher rates than men do. This suggests that the labor market does not offer equality of opportunity and equal treatment for women.

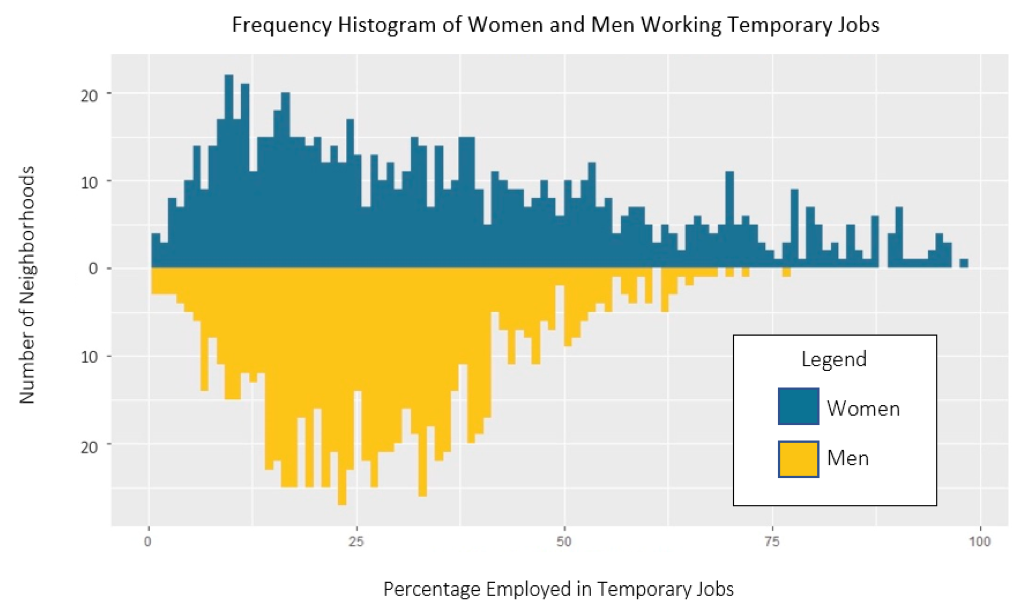

The percentage of employed women working in temporary jobs ranges from less than 1% to 98%, neighborhood to neighborhood (See Figure 2, below). The mean for all neighborhoods is 35% and in half of the 830 neighborhoods, the rate of women working temporary jobs is 30% or below. However, in ten percent of the neighborhoods, 70% or more of employed women work temporary jobs. When the availability of secure employment varies this much from place to place, where one lives can become a source of economic insecurity. If there were complete spatial equality, the rate of women working in temporary jobs would be equal from neighborhood to neighborhood and you would not see this incredibly large range.

For men in temporary contracts, the range is a bit narrower: from less than 1% to 77% (See Figure 2). The average is 28%. In three-quarters of the neighborhoods, the rate of men working under temporary contracts is 37% or below. Although there are clear disparities between neighborhoods, with men in some neighborhoods working in temporary jobs at very high rates, the neighborhoods with very high percentages of men in temporary contracts are outliers. It is only at the 95th percentile that more than half of men work in temporary contracts. What this means is that 95% of neighborhoods are to the left of the 50% mark in Figure 2 (looking just at the bottom half of the graph which shows only the rates for men). The neighborhoods that you see to the right of the 50% mark (again, referring only to the bottom half) make up just 5% of the neighborhoods in the GCR. Meanwhile, there are many more neighborhoods where more than half of women work in temporary jobs, and the range for women extends much higher than 77%, all the way up to 97%. There are 65 neighborhoods where more than 77% of women work in temporary jobs: these neighborhoods with surprising numbers of women working in temporary jobs are the focus of the section below.

Gender Gaps in the Most Precarious Neighborhoods

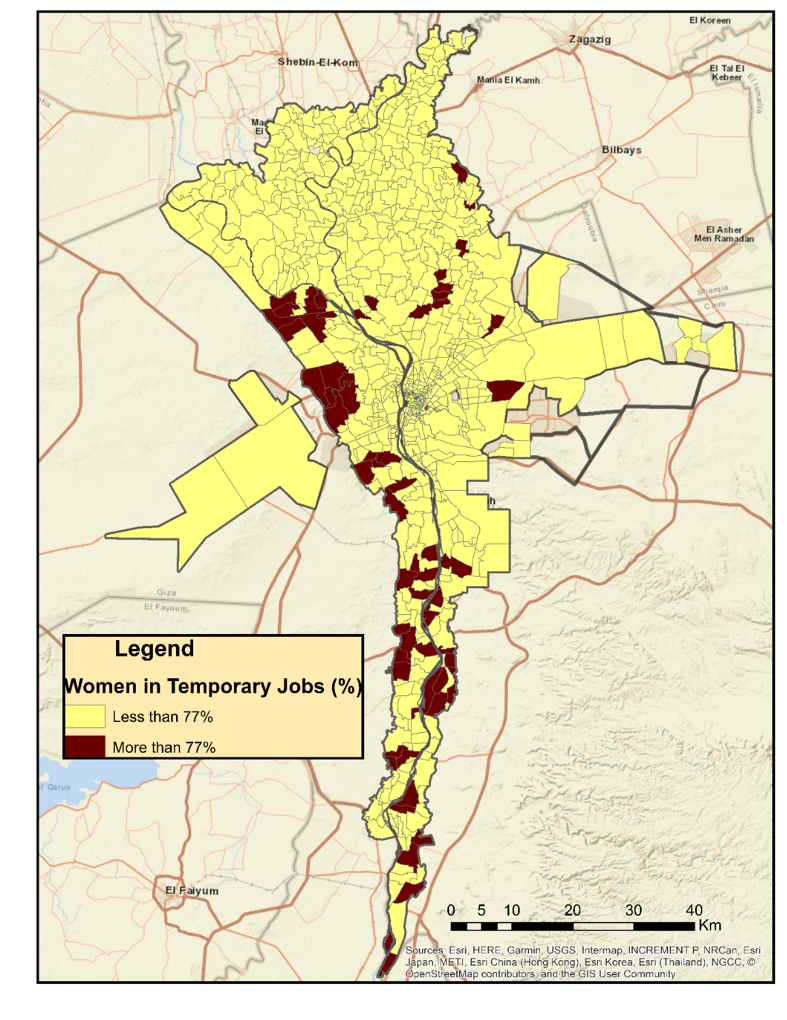

As discussed in the section above, in neighborhoods suffering from a higher degree of overall precarity in the sense that there are few permanent job opportunities, employed women still work in temporary positions at higher rates than men do. Again, the highest percentage of men working temporary jobs in any neighborhood is 77%. However, as we saw in Figure 2 (above), there are 65 neighborhoods where more than 77% of employed women work in temporary jobs. Of these neighborhoods, 59 are rural and 6 are urban. Our dataset includes more rural neighborhoods than urban neighborhoods (452 and 376, respectively), but rural neighborhoods are disproportionately represented amongst those with extremely high rates of women working in temporary employment. Map 5, below, shows where these neighborhoods are located. The majority of these neighborhoods are in Helwan, and as we move further north most are west of the Nile. Some of the neighborhoods are located in the north-eastern rural areas, and a few (the six urban neighborhoods) are right in the middle of the city.

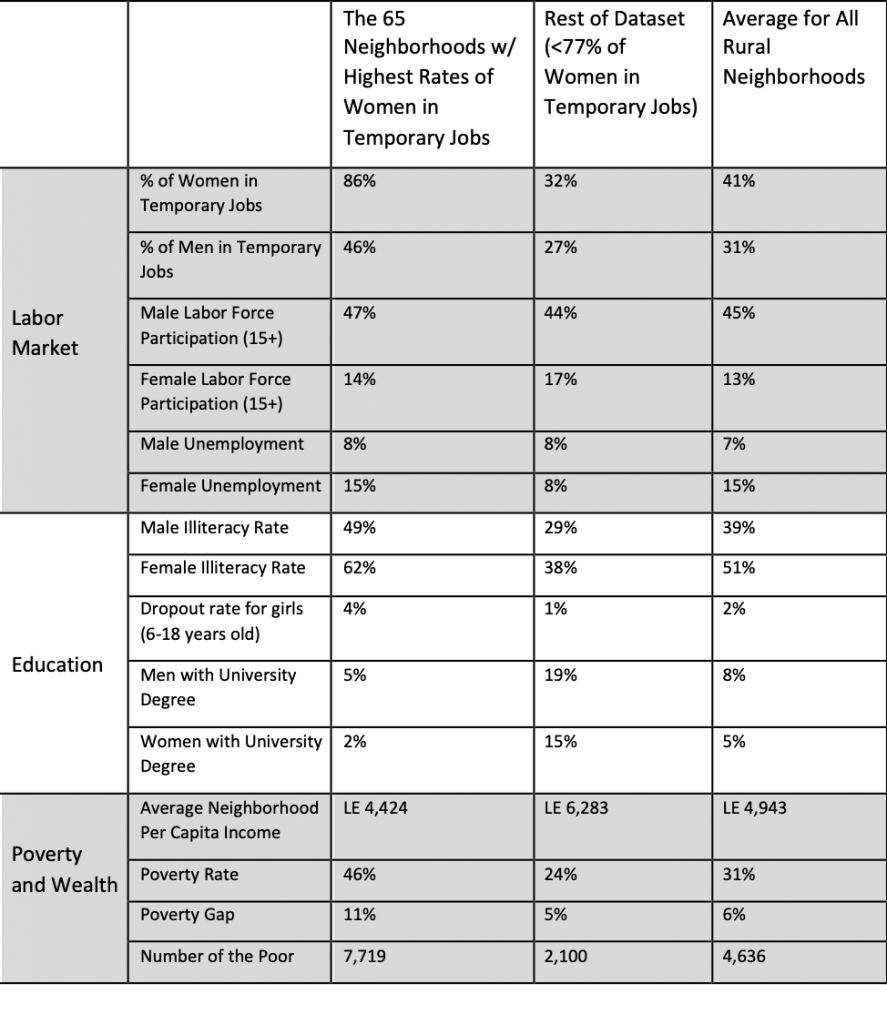

The 65 neighborhoods highlighted in Map 5 differ in many important ways from the rest of the dataset. Table 2 below compares the 65 neighborhoods that have the highest rates of women working in temporary jobs (Column 1) with the rest of the dataset (Column 2), as well as the average for all rural neighborhoods (Column 3) on metrics related to the employment, education, poverty, and wealth. We include the average for rural neighborhoods here to show that what we are capturing is not simply an urban-rural divide. On nearly every measure, these 65 neighborhoods are worse off than the average rural neighborhood. Additionally, the rate of women working temporary jobs in these 65 neighborhoods is double the average for rural areas, which tells us that the prevalence of temporary contracts in these neighborhoods is not simply a function of seasonal, agricultural labor; if it were, we would expect these neighborhoods to be much closer for the average for rural areas.

Compared to the rest of the dataset, the 65 neighborhoods with women working in temporary jobs at the highest rates (> 77%) have:

- Higher rates of men working in temporary jobs, but also the largest gender gap. Unsurprisingly, in the neighborhoods where women work in temporary jobs at the highest rates, men do so as well (we also saw this above, in Maps 3 and 4). However, the difference in the percentage of employed men versus employed women working temporary jobs is the largest in these 65 neighborhoods, by far. In these neighborhoods, the gender gap is 40 percentage points, compared to just 5 percentage points in the rest of the dataset and 10 percentage points for the average rural neighborhood. So although the high percentage of women working temporary jobs in these neighborhoods is driven in part by the reality of the types of jobs in the labor market itself, the very large gender gap here compared with other neighborhoods tells us that men manage to obtain the relatively limited supply of higher security, permanent jobs while women find themselves in much more precarious positions.

- Slightly higher rates of male labor force participation on average, but slightly lower rates of female labor force participation. If male labor force participation differed dramatically between these three groups, there might be important differences in the availability of jobs (overall) driving the disparities in the percentage of women working in temporary contracts. The rate of male labor force participation is roughly equal between these three groups. This indicates that the number of jobs available is likely comparable across these groups; the difference lies in the level of job security, which we can infer based on differences in the rates of temporary employment. Notably, the male labor force participation (ages 15+) does not exceed 50% in any of these three groups, reflective of the high unemployment rates in the GCR and the large number of dropouts from the labor force that are not included in official labor statistics. The rate of female labor force participation is just 14% in these 65 neighborhoods, which is slightly lower than the rest of the dataset (17%). It is approximately on par with the average for rural neighborhoods (13%).

- Approximately equal rates of male unemployment, but much higher rates of female unemployment. Like male labor force participation, the rates of male unemployment are approximately equal between these three groups. However, we see large differences when it comes to female unemployment. While female labor force participation is not particularly high anywhere in the GCR, the average female unemployment rate is relatively high in these 65 neighborhoods and also in rural neighborhoods (15% for both). This is nearly double that of the rest of the neighborhoods in the dataset which stands at 8%, equal to the average male unemployment rate in these neighborhoods.

There are several possible explanations as to why female unemployment is so much higher in the neighborhoods where the majority of employed women hold temporary jobs compared to the rest of the dataset. First, precarious employment by its very nature will eventually lead to higher unemployment rates. Contracts expire, jobs disappear, and workers are cast out of the labor force. Second, if temporary work is the most common type of employment in the neighborhood, it could be the case that women are turning down available jobs in hopes of finding something more permanent. Third, higher levels of poverty in these neighborhoods may mean that more women find it necessary to seek employment. In households where men have higher incomes and job security, women might choose to exit the workforce (and therefore are not included in unemployment statistics). In contrast, in less well-off neighborhoods, women may not have the option to stay home. This means that more women are seeking work, but there are simply not enough opportunities, driving up the unemployment rate. Household level data and more information on neighborhood labor markets and job opportunities could help us uncover the causal story here.

The differences are not confined to the labor market. There are also major differences when it comes to education. Although education does not guarantee employment let alone job security, it is still an important factor (Tadamun 2018). In neighborhoods where the vast majority of employed women work in temporary jobs, there are:

- Much higher illiteracy rates on average, but especially amongst women. Nearly half of men are illiterate in these 65 neighborhoods, while less than a third are in the neighborhoods in the rest of the dataset. As for women, more than 60% are illiterate in these neighborhoods, compared with less than 40% in the rest of the dataset. In addition to higher rates of illiteracy overall, the illiteracy gender gap is larger: 13 percentage points compared with 9. This gender gap is comparable to the gender gap in rural neighborhoods on the whole, which stands at 12 percentage points. However, the illiteracy rates in these 65 neighborhoods are still higher than the average rural neighborhood by more than 10 percentage points for both men and women.

- Higher rates of dropouts for girls (6-18). The percentage of girls between the ages of 6 and 18 that have dropped out of school is higher in these 65 neighborhoods than in the rest of the dataset and also compared with rural neighborhoods. A 4% dropout rate might not seem astronomical, but when we compare this to the 1% rate of dropouts for the rest of the dataset, we can imagine the effect that this disparity might have in the future in exacerbating inequalities between these neighborhoods. The dropout rate for boys (not shown) is approximately equal.

- Much lower percentages of women with a university degree. Only a very small percentage of women (2%) have a university education in the neighborhoods where women work in temporary jobs at high rates. This is slightly lower than the average rural neighborhood (5%), but much lower than the average rate for the rest of the data (15%). Recall too that there are large gaps between these three groupings when it comes to illiteracy. Rates of illiteracy are highest amongst the older segments of the population; even as Egypt begins to close gender gaps and geographic disparities in primary schooling and increasingly secondary education, the gaps in illiteracy remain amongst older segments of the population and access to university education is still constrained by poverty and geography. The trends for men when it comes to university education are the same, and the gender gap is approximately equal for each group.

Although our data comes from a single point in time and thus, determining causality is not truly possible, it is not a stretch to argue that education and employment exert effects on income. In these neighborhoods we see:

- Much lower per capita incomes. It should not be surprising that the 65 neighborhoods with women working in temporary jobs at the highest rates have the lowest average per capita income of any of the three groups, more than LE 1,800 less than the neighborhoods in the rest of the dataset and more than LE 500 less than the average rural neighborhood.

- Much higher rates of poverty and deeper poverty. Nearly half of the population in these neighborhoods lives below the poverty line, compared to about a quarter in the rest of the dataset and a third in the average rural neighborhood. Not only are poverty rates higher in these neighborhoods, but people live much further below the poverty line. The “poverty gap” is a measure of the depth of poverty: it is distance between the average income in the neighborhood and the poverty line. For example, the poverty line in Egypt is currently LE 800 (USD 44.72) per person, per month. So for a neighborhood with a poverty gap of 5%, an average increase of LE 40 per individual per month would bring the per capita income of the neighborhood up to the poverty line (40 is 5 percent of 800). The poverty gap in the 65 most precarious neighborhoods is 11%, approximately double the average for the rest of the dataset and the average rural neighborhood. With a poverty gap of 11%, an increase of LE 88 per individual per month is necessary to bring the per capita income up to the poverty line.

- Larger numbers of the poor. There is an average of 7,719 people living below the poverty line in these neighborhoods, compared to just 2,100 in neighborhoods in the rest of the dataset and 4,636 in the average rural neighborhood. The number of the poor is an important metric when discussing issues of spatial justice. In the most precarious neighborhoods, a larger number of people on average are impacted by poverty compared to other neighborhoods in the dataset.

In sum, the neighborhoods with extremely high rates of women working in temporary jobs are on average much more disadvantaged than the rest of the neighborhoods in the GCR on a number of other metrics, and also worse off than the average rural neighborhood. Although our data on the labor market is limited in that we cannot determine the industries that may be concentrated there or the types of jobs that are available, the very different employment outcomes tell us that job opportunities and security vary from neighborhood to neighborhood. Some labor markets are more precarious than others, especially for women as shown by the gender gap in temporary employment. Labor markets in some places are also much more inaccessible to women; the gender gap in unemployment rates is evidence of this. Moreover, the disparities in illiteracy and university education imply that educational opportunities are limited in certain places which likely spills over into future employment. The higher rates of dropouts in these neighborhoods all but ensures this inequality will continue into the future if this trend does not abate. Finally, all of this leads to differences in wealth, poverty and household security. In the neighborhoods where women experience the highest levels of precarious employment, they also live in the most precarious conditions.

Women and Domestic Work

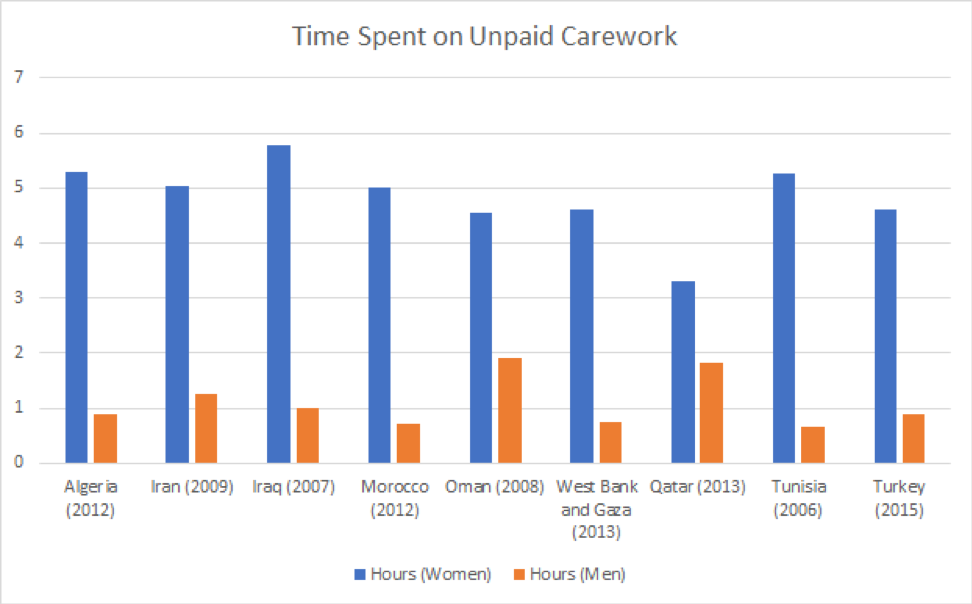

As a final note, we turn to the household. In addition to unfavorable conditions for women in the workplace and increased precarity in employment, women also face inequity in the distribution of household labor, engaging in domestic work at much higher rates than men and spending more time every day on unpaid care work than men. This holds true for most countries in the MENA region, where women are spending up to five more hours than men every day on unpaid domestic work. Perhaps surprisingly, the distribution of household labor is most equitable in the Gulf. On the other hand, Tunisia has one of the least equitable divisions of household labor, in spite of the fact that women in Tunisia have the highest rates of labor force, political and civil society participation. What this tells us is that inequality in the private sphere may persist even when there are important gains for women’s participation in public life.

- Figure 3: Time Spent on Unpaid Care Work, Women versus Men. Data is from national statistical offices or national database and publications compiled by United Nations Statistics Division, and as reported by the World Bank. The year in parentheses after the country name indicates the year of the survey.

Although the MENA region has the greatest gender disparities when it comes to time spent on unpaid care and domestic work, it is not as though other world regions have achieved equity. For example, an OECD report comparing world regions shows that in Western Europe, women spend four hours per day on average on unpaid care and domestic work, while men spend only two (Ferrant, Pesando, & Nowack 2014). The report also finds that around the world, higher rates of unpaid care work are associated with lower levels of female labor force participation, increased “occupational downgrading,” where women accept employment below their skill-levels to accommodate household responsibilities, and larger gender wage gaps.

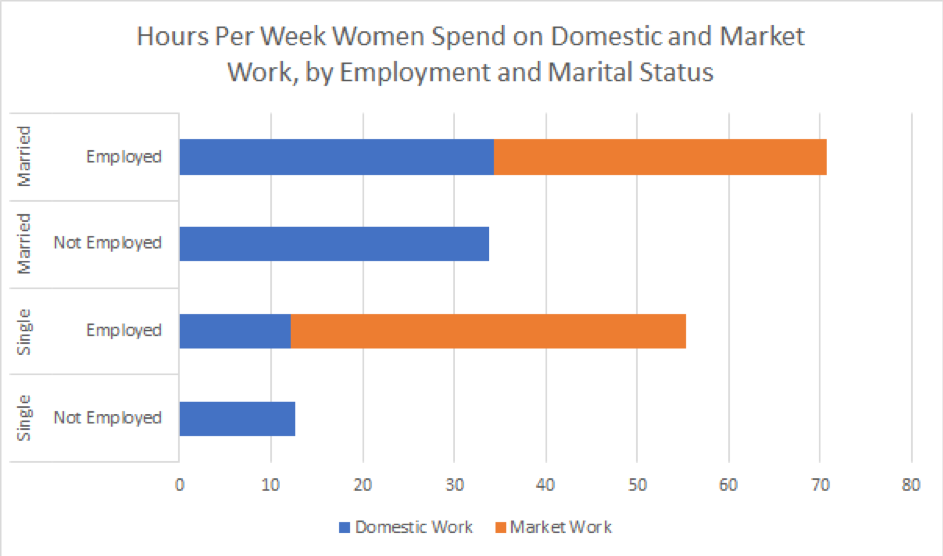

In the case of Egypt specifically, we can examine the interaction between marriage and employment on a woman’s domestic work responsibilities. The 2012 Egyptian Labor Market Panel Survey (ELMPS) survey shows married women who are employed put in a half hour more of domestic work than their unemployed, married counterparts (Figure 4). In effect, married women are working two jobs: domestic work and market work, but they are only paid for one. While married women do work 7 hours fewer than single women in paid, market labor, they spent approximately three times as many hours on domestic work as single women.

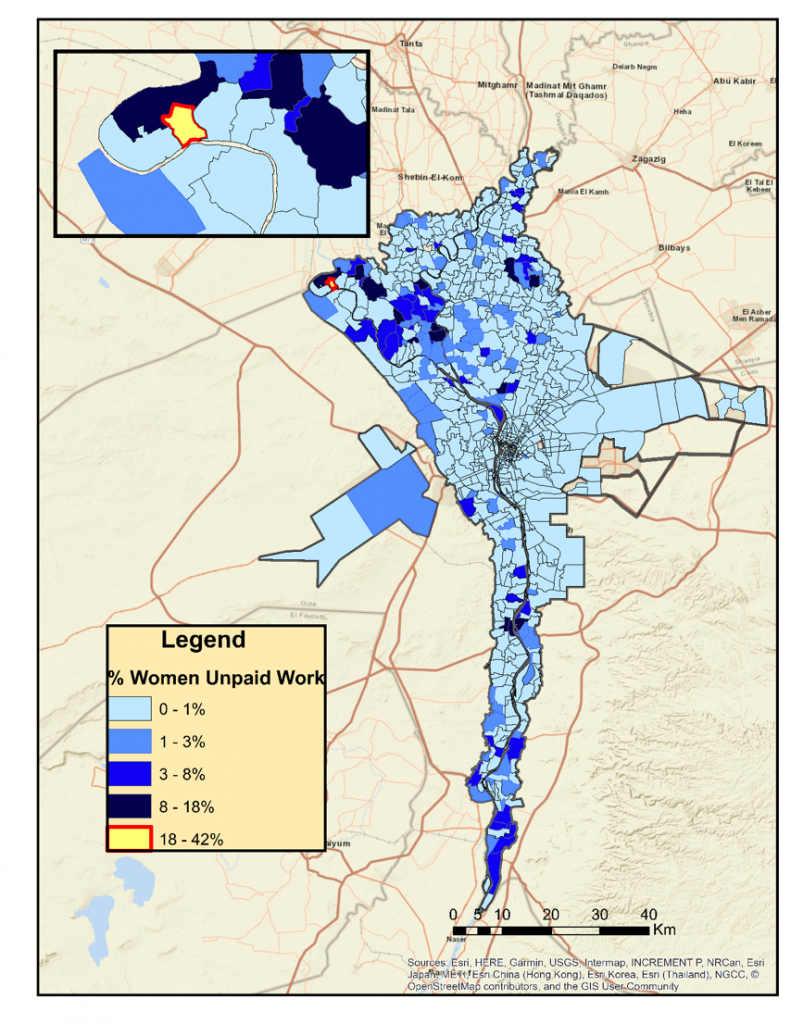

In addition to the fact that women are not paid for their domestic labor, our data shows us that there are a few neighborhoods where women engage in high rates of unpaid market labor. Map 6 shows the percentage of women who report that they are employed, but are not paid. More than likely, this represents women who work in care work for close relatives, or who are employed in family enterprises, although we cannot say this with certainty. What we do know is that because these women are considered “employed,” they are counted in labor force participation statistics in spite of the fact that unpaid labor does little for economic mobility. Although there is not that much variation throughout the GCR, with the vast majority of neighborhoods showing single-digit rates of women in unpaid work, there is one neighborhood in the upper-northwestern part of the map, Kafr Al-Traynah in the Menoufia governorate, where a full 42% of employed women are unpaid. The inset map shows that in the area surrounding Kafr Al-Traynah, there is variation between neighborhoods when it comes to the rates of women in unpaid work; however, these neighborhoods are relatively homogenous when it comes to other indicators, such as poverty, per capita incomes, wealth and other employment statistics, such as unemployment and temporary jobs. Although we cannot isolate a cause, what we do know is that the labor market in this particular neighborhood is not providing the sorts of opportunities necessary for women to participate in the paid labor force, contributing to precarity.

- Map 6: The percentage of employed women working in unpaid jobs. Only two neighborhoods fall into the last category, with one neighborhood reporting a rate of just above 18% and the other neighborhood (highlighted in red), 42%. In the vast majority of neighborhoods, less than 1% of employed women are engaged in unpaid work.

Conclusion

The solution to precarity is security. A first step would be to promote more permanent labor contracts particularly in industries or neighborhoods with a geographic concentration of precarity. Even if temporary contracts are here to stay, there must at least be some degree of regulation to bring about higher levels of security within the confines of such employment agreements. Otherwise, neighborhoods where temporary contracts are the norm will more than likely remain disadvantaged. Our analysis not only shows that precarious employment is geographically concentrated, but it is often overlaid with other types of inequalities such as high levels of poverty and low levels of education, speaking to the multidimensional nature of spatial inequality.

There are two possible explanations for why we see such a high concentration of temporary contracts in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods. The first has to do with the nature of temporary contracts themselves: lower incomes, fewer benefits, and less job security all contribute to poverty. In this case, vulnerable employment leads to economic vulnerability. The other explanation has to do with the decision-making processes of employers: employers may take advantage of residents in socioeconomically depressed neighborhoods, under the rationale that any employment—even precarious, poorly compensated employment–is better than no job at all. In this case, the already precarious position of neighborhood residents opens the door for predatory practices. This might be especially problematic in neighborhoods with high illiteracy rates and few educational opportunities.

Because our data is from one point in time (2006), we cannot establish causality. More than likely, both processes are at work, further compounding the issue and producing ever increasing inequalities between neighborhoods. Policies must reign employers in to prevent them from taking advantage of the most vulnerable of workers and solidifying inequalities between places. Utilizing mapping strategies to locate neighborhoods with the highest rates of temporary employment along with the highest rates of poverty would allow policy makers to target the neighborhoods most in need of equitable employment options and hold employers in those places accountable. Utilizing multiple metrics of inequality, in addition to considering the spatial dimension of inequality, offers the most efficient way of reducing the spatialized precarity we see between neighborhoods.

However, any policy that puts the onus on employers to offer higher compensation and better benefits should be at least somewhat sensitive to the capacity of the employer to do so. Large enterprises, such as factories, boast cheap employment in order to attract higher levels of investment and generate higher profits. Factories, especially textile factories, often employ women at higher rates, specifically because they can pay them less. These jobs may be one source of the gendered nature of precarious employment in the GCR. Large enterprises have the capacity, but not necessarily the willingness, to provide better opportunities to workers. Smaller and often family-run enterprises such as artisanal workshops, carpentry and car repair shops may wish to do more to support their employees, but do not have the capacity to do so. Large enterprises should be the primary targets of any policies that require increased efforts on the part of employers to provide more for workers. Neighborhoods with smaller enterprises may benefit from other types of interventions—such as public investment in services–to increase economic security.

Another important step is to eliminate laws that excuse employers from providing benefits dependent on sector: for example, the Egyptian Labor Law of 2003 expressly denies women working in agricultural jobs maternity leave (Article 97), and child labor laws that prevent children under the age of 14 from working are not applicable in the agricultural sector (Article 103). Our mapping showed us that the highest rates of temporary employment are in rural areas, meaning that certain exemptions to labor laws may disproportionately impact women in already precarious jobs, exacerbating economic insecurity. However, and as we discussed in the introduction to this brief, the government loosened many important labor regulations and protections across all sectors as a result of neoliberal reforms and privatization. Providing exemptions from current labor regulations for certain sectors leads to more spatial inequality between places, but deregulation has led to increased precarity on the whole.

Finally, although the low rates of female labor force participation and high unemployment in the in GCR are a real issue, it is important to avoid attempts to increase female labor force participation at all costs, regardless of the availability of decent work. A gender-sensitive approach understanding the spatial distribution of precarity in the labor market might help to avoid seeing more and more women in temporary contracts or otherwise vulnerable employment. Our analysis of the neighborhoods where women work in temporary jobs at much higher rates than men showed us that these areas have much higher rates of female illiteracy and education, higher rates of poverty, and deeper levels of poverty than the average for the rest of the GCR as well as the average rural neighborhood. The creation of more temporary jobs could make these issues worse. Any new jobs should not replicate the current problems in the labor market, and should provide the necessary protections to create security, rather than reproduce precarity.

For women, the solution to precarious employment involves additional gendered protections, especially those related to maternity and child services. Currently, the law guarantees three months of paid maternity leave to women working in the public sector (Law No. 12 of the year 2003, Article 91). The new draft Egyptian labor law (not yet passed) would increase the duration of leave to four months and would give women working in the private sector the same maternity leave benefits as public sector employees. However, paid maternity leave is still granted only twice in a woman’s tenure at a job. The fertility rate in Egypt is currently 3.26, meaning that on average, women give birth to three children (UNDP 2017). This restriction is therefore not in line with the current reality of childbearing and families in Egypt.

Maternity leave protections do not apply to the informal sector. The majority of women in the informal sector are illiterate and there is a direct correlation between lower educational attainment and higher fertility rates (Nazier and Ramadan 2016). In the neighborhoods we examined with the highest rates of women working in temporary jobs, the average illiteracy rate was 62%. These neighborhoods in particular may be places to evaluate the experience of working mothers, as well as women who drop out of the labor force after giving birth, and craft policies attuned to their needs.

There are also no provisions for paternity leave (which are rare the world over). But as we have shown, married, working women in Egypt dedicate more than 70 hours a week on average to combined market work and domestic labor. Paternity leave has the potential to shift norms surrounding the responsibility of childcare, as well as the distribution of household labor. This would afford women more opportunities to participate in the labor force that do not depend on sacrificing quality of life by adding the demands of market labor to unequal household duties.

Importantly, there are no protections that guarantee women the right to return to work after maternity leave. In other words, women can receive paid leave for the duration of three (and perhaps soon, four) months and then be terminated from their jobs. And while the labor law stipulates that employers with more than one hundred female workers must establish a nursery school or assign one (Article 96), smaller enterprises have no obligation to do so, meaning that the make-up of the establishment women work for determines the services that they receive. So although Egypt has more generous maternity protections than many countries, there are still loopholes that employers can use to place women in a precarious position: particularly the ability to fire women after maternity leave.

In sum, a multidimensional approach to precarity in the labor market is necessary for finding solutions that will create better outcomes and more security for all workers. It is necessary to consider the spatial dimension to see where precarity is concentrated and target policies to the areas that stand to benefit most, particularly places where there are overlapping inequalities. The type of intervention is often dependent on the nuances of the labor market: whether enterprises are small or large, and whether it is the formal or informal sector, amongst other considerations. Precarious employment disproportionately affects women, so a gender-sensitive approach is the only way to ensure that reforms benefit the most vulnerable workers. There are no one-size-fits-all policy solutions but all policies should be sensitive to the local context and promote greater equality between all places, for all workers.

Featured image: Photo by Hossam el-Hamalawy, taken May 9th 2007

References:

Arnold, D., & Bongiovi, J.R. (2012). Precarious, Informalizing, and Flexible Work: Transforming Concepts and Understandings. American Behavioral Scientist, Vol 57(3), pp. 289-308.

Assaad, R. & Arntz, M. (2005). Constrained Geographical Mobility and Gendered Labor Market Outcomes Under Structural Adjustment: Evidence from Egypt. ًWorld Development, Vol. 33(3), pp. 431-454.

Assaad, Ragui. (2015). “Women’s Participation in Paid Employment in Egypt Is a Matter of Policy Not Simply Ideology.” Egypt Network For Integrated Development Policy(Brief): No.22.

Dimova, R., Elder, S., & Stephan, K. (2016). Labor Market Transitions of young women and men in the Middle East and North Africa. Work4Youth Publication Series, Vol. 44.

Ferrant, G., Pesando, L.M., & Nowacka, K. (2014). Unpaid Care Work: The missing link in the analysis of gender gaps in labour outcomes. OECD Development Centre.

Fudge, J. & Owens, R. (2006). Precarious Work, Women, and the New Economy: The Challenge to Legal Norms. Hart Publishing.

International Labor Office (ILO). 2018. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends for Women 2018 – Global snapshot International Labour Office – Geneva: ILO, 2018 Retrieved from: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_619577.pdf

Moghadam, V. (2010). Chapter 5: Global restructuring and women’s economic citizenship in North Africa. Gender and Global Restructuring: Sightings, Sites, and Resistances. 2nd ed. ed. Marianne Marchand & Anne Runyan. Routledge, London.

Nazier, H. & Ramadan, R. (2016). Women’s participation in labor market in Egypt: Constraints and opportunities. The Economic Research Forum (ERF) Working Paper Series, Working Paper No. 999.

Neilson, D. (2015). Class, precarity, and anxiety under neoliberal global capitalism: From denial to resistance. Theory & Psychology Vol. 25(2), pp. 184-201.

Ortiz-Ospina, E., Tzvetkova, S., & Roser, M. (2018). Female Labor Supply. Our World in Data. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/female-labor-supply

Rodgers, Gerry & Rodgers, Janine. 1989. Precarious Jobs in Labour Market Regulation: The Growth of Atypical Employment in Western Europe. Geneva: ILO.

Social Institutions & Gender Index: 2014 Synthesis Report. (2014). OECD Development Centre.

Tadamun. (2018). Inequality of Opportunity in Cairo: Space, Higher Education, and Unemployment. Retrieved from: http://www.tadamun.co/inequality-opportunity-cairo-space-higher-education-unemployment/?lang=en#.Xef2sJJKjjA

The Solidarity Center. (2010). Justice for All: The Struggle for Worker Rights in Egypt.

United Nations Statistics Division (2015). Proportion of time spent on unpaid domestic and care work, female (% of 24 hour day). [data file] Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SG.TIM.UWRK.FE?view=chart

United Nations Statistics Division (2015a). Proportion of time spent on unpaid domestic and care work, male (% of 24 hour day). [data file] Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SG.TIM.UWRK.MA

Comments